Humus, 2019

digital video, colour, sound

duration: 11:13 minutes

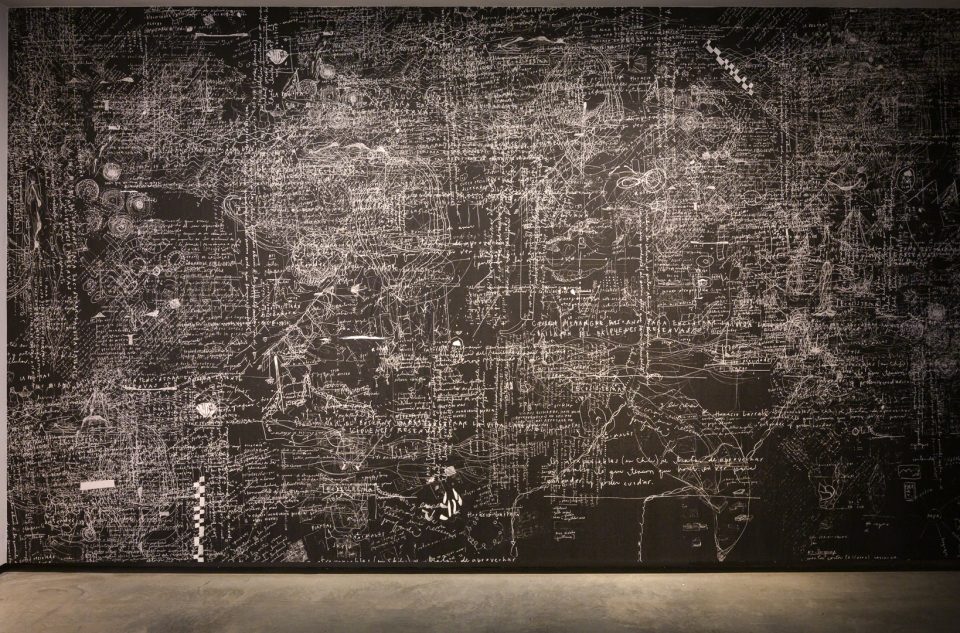

Wallpaper, 2021

high resolution digital latex printing on wallpaper with washable vinyl coating

Black Bark I, 2021

ink and natural elements printed on cotton Hahnemühle matt fine art paper

Black Bark II, 2021

ink and natural elements printed on cotton Hahnemühle matt fine art paper

What remains of one, 2017

cotton, linen and canvas fabrics restored with silk crepeline conservation fabric

What remains of the other, 2017

cotton, linen and canvas fabrics restored with silk crepeline conservation fabric

Courtesy the artist

Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with assistance from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Chile and the Catholic University of Chile

Paula de Solminihac’s works are about process, always in flux, constantly transformed by the elements into something new.

‘In 2017, I planted two cherry trees in my studio yard. When they shed their last leaf, I took the trees out of their pots, which were made of fabric. The eroded remnants of the pots were taken to a photographer’s studio to be captured open like a flower in a herbarium. I inverted those photos so the white became black and the black became white. Then I made these photos into little lumps that I buried in my garden for some time. Black Barks is a sequence of containers that contain each other and whose creative process lies in the contact with the silent transformative powers that happen in the soil and that end when the photos are opened to be shown.’ – Paula de Solminihac

Fogcatcher, 2018-2021

netting of canvas strips and linen dyed with natural and synthetic tints

Worm Column, 2021

red and white terracotta

Pond, 2021

enamel black ceramic

Courtesy the artist

Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with assistance from the Catholic University of Chile and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Government of Chile

“Kamanchaka”, is a word of the Aymara Indigenous peoples of the Andes and Altiplano region. It means “darkness” and describes a thick fog typical of the Atacama Desert that forms in the Pacific Ocean, rises through the coastal mountain range and vanishes when it enters the central valley. The work is inspired by Solminihac’s observation of invisible relationships of mutual symbiosis between different forms of existence. In this fogcatcher, Solminihac brings attention to this device that imitates the process of collecting stems and leaves, in order to observe the invisible water in the air, an essential water resource in the most arid desert in the world and to the invisible architecture of the earth’s soil built by earthworms. The paths that earthworms leave behind through their circulation allows the formation of storage pores for groundwater, an invisible water resource which constitutes the world’s largest reserve of fresh water for the future. Exposed to the elements in The Cutaway, the fogcatcher includes a textile net to catch water, a column of ceramic worms and a black ceramic pond. The worm forms have been made through collaborative workshops with students in Chile symbolising processes of cooperation and interdependence leading to what de Solminihac refers to as an “energetic cycle where humans and nature constitute a whole”. And the black pond, made of melting and self-consuming vessels, are the paradox of any form of containment.

“So if the lesson that ceramics gives us allows us to stop thinking about opposites, the next step could be to think that these opposites are connected to each other and that if I follow the branches of the tree of life, I will be able to realise that everything is interrelated. and that they are not only related but also dependent on each other.”

Dew

Paula de Solminihac, 2021

To the south of the Atacama

Desert, a very particular

phenomenon occurs, which

helps to compensate with

human ingenuity for the aridity

of the territory. On the coasts

of these places where little is

cultivated, the masses of humid

air released by the Pacific

Ocean form dense morning

mists called kamanchaca

(Aymara word that means

darkness), and that by effect of

the Pacific anticyclone circulate

towards the interior where they

end up vanishing.

The Cavern

the spirit dwells in the void and is embraced by the weight of things.

Life arises from biological evolution and this last one from a random play of physical and chemical processes. In this dynamic cycle, minerals become animals and these in turn become rock, rock that later, with geological time, will be the substance with which new organisms will make their bodies.

Burying the dead, descending into the mines or delving into the intimacy of the earth, it seems that our ancestors always knew that we animals are also mineral beings and that death and life find a common place in the cavities that the earth offers.

The caverns, dens, burrows and grottoes make up the varied counterforms of matter, terrestrial and animal, where the vestiges of time are stamped, the humidity of life is preserved and where darkness progressively erases the drawings of the conscious structure so that the spaces of reverie gain warmth.

The Cavern is an installation that invites us to turn our gaze towards these indeterminate spaces of inner life.

The work seeks to create an enveloping space from the remains of the artist’s searches and chores, among the drawings in her notebooks, the materials she took to wrap other materials, to plant, to model forms and the residual images that were left over from those daily processes.

Entering the cavern is like entering the darkness of the womb where there is no order of figure and background; where there is no history, but images that have renounced the linear narration of time, preferring the state of permanent oneiric formation, knowing that possibly, as improbable forms, they will end up disintegrating into their elements, returning to the general tendency to entropy from which they once emerged by chance.

– Paula de Solminihac