On mimesis*

mimesis opens one’s sensory awareness to ‘other’

mimesis is a process of attunement to the more-than-human

mimesis is a meeting point, a space-in-between

mimesis is a way of directing attention to earth-others

mimesis is a method of thinking-with and feeling-with

mimesis is an embodied practice of becoming-with

______________________

*

A basic theoretical principle in the creation of art, from Ancient Greek, the term can mean both ‘imitation’ and ‘representation’, originating with Plato, who discussed mimesis as an element of the dramatic arts, suggesting that when actors impersonate characters in a play, they render themselves vulnerable to absorbing the qualities of those characters. Outside of western philosophy, practices of mimesis have existed throughout time in vernacular culture, in music, movement and dance, emerging through an intimate connection with the more-than-human – mimesis of various critters, water, weather, and complex multispecies entanglements and assemblages. What might these embodied knowledges teach us about processes of unbecoming and becoming, of co-existence, kinship, and of living and dying well on a damaged planet?

Seals’kin, 2022

single channel moving image and stereo sound

19:14 mins

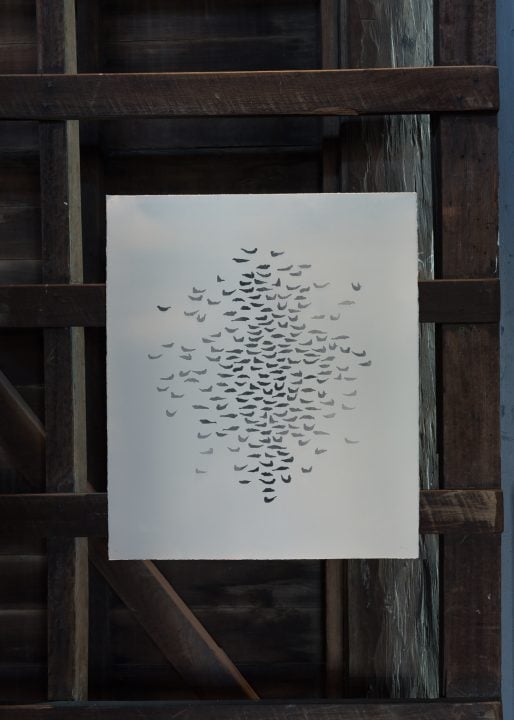

Seals’kin (choreographic visual score), 2022

flock screenprint on somerset antique white

Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous support from Creative Scotland and from the UK/Australia Season Patrons Board, the British Council and the Australian Government as part of the UK/Australia Season and generous assistance from Frame Finland

Hanna Tuulikki’s short film Seals’kin is a sonic and choreographic meditation on loss, longing, transformation and kinship, shot on location in coastal Aberdeenshire in Scotland. At the mouth of the river Ythan, where the freshwater meets the North Sea, hundreds of grey and common seals haul out on the estuary banks. Here, Tuulikki explores with her body what it might mean to become-with-seal, drawing on myths of human-seal hybridity and folkloric musical practices to offer alternative forms of mourning through sensuous identification with more-than-human kin.

For as long as we have inhabited the earth, humans have shared the seas, coasts and islands with seals – web-footed mammals adapted to life in the water. In places where people depend (or once depended) on the sea for their livelihood, seals are intricately entangled with peoples’ beliefs. In Ancient Greek mythology, the eerie calls of grey seals carried on the wind were probably the original siren voices, luring unwitting sailors to their deaths on the rocks. Shape-shifting is a recurrent theme, and nowhere are there more tales of human-seal transformation than in Scotland.

In Scottish folklore, mythical seal people known as selkies are said to shed their sealskins and step from water as humans, until mysteriously disappearing back to sea. The sealskin is essential to the act of transformation and, on visiting the human world, if their skin is lost or stolen, a selkie may end up trapped on land in human form. In their watery domain, a selkie distressed by the slaughter of a fellow seal may seek revenge on a human seal hunter, capsizing a boat in retribution, while a benevolent selkie might take pity on a lost mariner caught in a storm, offering shelter in their kingdom under the sea. Selkie stories were passed down from generation to generation and, embedded within the folklore are a number of musical traditions that appear to blur the line between human and seal, including melodies which imitate their plaintive sounds, and haunting seal-calling songs sung to attract seals to the shore.

Perhaps these selkie stories of loss and longing helped to alleviate the feelings of sorrow brought on by a sudden death in the community, or from relatives lost at sea. Musical practices of singing to or with seals may have maintained a felt connection with the dead through the fostering of kinship with seals and selkies, thought by some to be the souls of the departed. But as folkloric coping mechanisms for grief, how might these stories and songs help us to come to terms with the collective and personal tragedies of the present pandemic? And furthermore, how might they help us to navigate the sorrow of ecological or climate grief?

By virtue of having a body, we are all vulnerable to loss, and the more intense the love was for a person, being, place or thing, the greater the grief. Our response to loss moves us, changing us in ways we could not imagine; it leaves us more open to other bodies, exposes our shared vulnerability and finitude, and fosters meaningful connections. The work of mourning then, is politically and ethically transformative, for it implies empathy, obligation and responsibility. By directing our attention to more-than-human beings and places that are often excluded from the realm of the grievable, we can begin to nurture new forms of kinship and rethink more hopeful futures.

In Seals’kin, Tuulikki draws on her own recent experiences of loss to reimagine a contemporary mourning rite. Referencing traditional selkie tales as bereavement allegories and seal calling songs as practices of making kin, she adopts the sealskin as a powerful ritual object to explore how grief can open out new ways of knowing and being that stretch beyond human bodies into a visceral connection with the more-than-human world.

– Hanna Tuulikki, artist statement, 2022