‘History versus memory, and memory versus memorylessness. Rememory as in recollecting and remembering as in reassembling the members of the body, the family, the population of the past.’

– Toni Morrison, Mouth Full of Blood: Essays, Speeches, Meditations by Toni Morrison, 2019. London: Penguin Random House, p. 323.

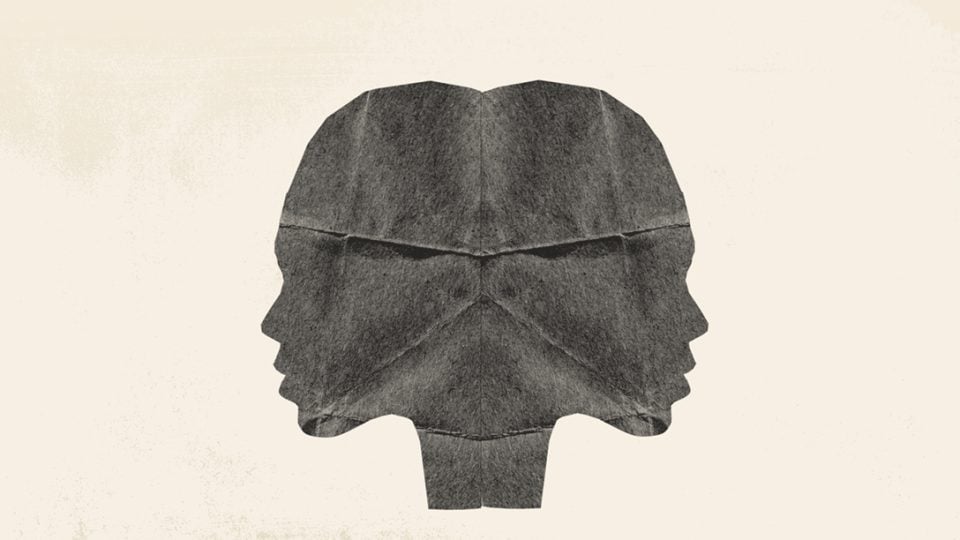

‘Rememory’ as coined by Toni Morrison in her novel Beloved is the theme and title for the 25th edition of the Biennale of Sydney. Expanding from the understanding of memory as ‘information retention with the passing of time’, ‘rememory’ works in the dark, from the residues and amputations of the past. In Morrison’s own context and research, it relates to chronicling African American history and how it upturns what is canonised as American history.

Approximating Morrison’s concept alongside the work of contemporary cultural practitioners – who engage with topics that have little to no benchmarks, precedents, and models – ‘rememory’ thus becomes an active present. The exhibition collaborates with artists and cultural workers who explore the collateral damage and side effects of historic events. Abandoning typical and linear storytelling, in which history and memories are presented through objectification, rememory is how we become subjects and storytellers of our collective present through events of the past.

In this upcoming edition of the Biennale, the exhibition and participating artists gather to present a polyphonic ‘rememory’, inspired by Sydney and the broader region. Works in the Biennale reflect on the region’s communities, Aboriginal peoples, and diasporas in relation to historic events. A call to shed known ‘stories’ about the place, the edition is akin to a patchwork in which artists have been invited to reflect on their own topoi, while also engaging with local communities, to highlight their histories of migration, exile, and sense of belonging. This is complemented by a specialised children and youth program that circulates these ‘rememories’ so as to retain them intergenerationally.

While scholarship and archives are extremely critical in unlearning and decoding the present, the exhibition supplants such rigour with assemblages of self-authorship and rememory, as proposed by Morrison and like-minded peers. The hope is to develop new knowledge that centres on unrecognised voices through non-canonical methods and embodied forms. Additionally, it is a proposition for a world of proximities through affect, and modalities of memory making.

‘The postcolonial today is a world of proximities. It is a world of nearness, not an elsewhere. Neither is it a vulgar state of endless contestations and anomie, chaos and unsustainability, but rather the very space where the tensions that govern all ethical relationships between citizen and subject converge. The postcolonial space is the site where experimental cultures emerge to articulate modalities that define the new meaning – and memory making systems of late modernity.’

– Okwui Enwezor, documenta11_Platform 5: The Catalogue, 2002. Berlin: Hatje Cantz, p. 44.