White Bay Power Station

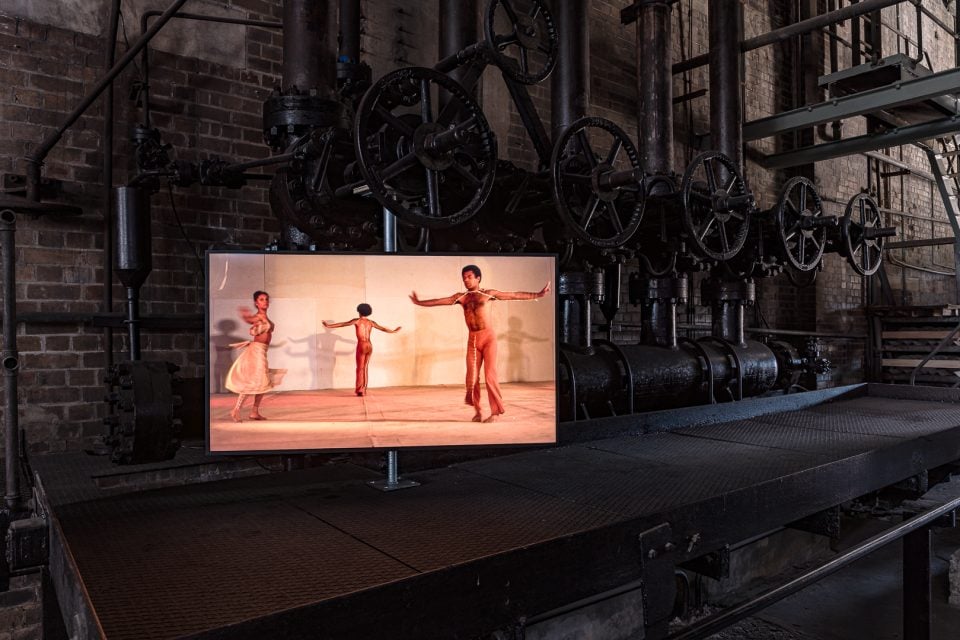

Publicity Photographs for Nigeria tour #1-#21, 1976

digitised images, three-channel projection

Presentation at the 24th Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous assistance from Simon Chan AM Art Atrium

Courtesy the artist and The State Library of NSW, Sydney

In the years following the independence of most countries on the African continent, more than 16,000 Black artists, performers, poets, and intellectuals descended upon Lagos (the Nigerian capital at the time) in a celebration of international Black unity that American magazine Ebony described as a “family reunion”. FESTAC ’77, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, featured the likes of Gilberto Gill, Stevie Wonder, Audre Lorde, Les Ballets Africains, Miriam Makeba and an Australian contingent of Aboriginal writers, filmmakers, cultural dancers, and a group from the recently created Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre (AIDT).

William Yang photographed the five dancers of AIDT (Lillian Crombie, Michael Leslie, Wayne Nicol, Richard Talonga, and Roslyn Watson) as they were preparing to travel to Nigeria to join the broader internationalist Black community of the time. Their intoxicating joy and happiness in these images embody the hope and dreams of Black Australian urban youth towards the movements for self-affirmation and Aboriginal empowerment in society during the Whitlam-era.

AIDT’s repertoire in Nigeria included dances with social commentary touching on subjects such as the Stolen Generation and the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, choreographed in Sydney by their professors, including Filipina dancer Lucy Jumawan.

According to Carole Y. Johnson, founder of NAISDA Dance College, the Australian delegation in FESTAC “could be the first participation of Indigenous Australians in international affairs in which they become a part (of) … initial organising.”

If one were to shake loose any given pocket of contemporary Australian culture over the last 50 years, it is William Yang who is most likely to come tumbling out. Camera perpetually in hand, he has captured the streets, parties, people, and personalities of Australia’s creative set with both the dogged curiosity of an interloper and the intimacy of an insider. At a time when Indigenous rights in Australia were becoming increasingly politicised, Yang’s photographs of this event position him not only as a documentarian but as an active participant in the celebration of Indigenous Australian culture as an international tour de force.

UNSW Galleries

Mother Driving, My Uncle’s Murder Series, 2008

Fang Yuen and Aunt Bessie, My Uncle’s Murder series, 2008

Fang Yuen and Business Partners, My Uncle’s Murder series, 2008

In Cane Fields, My Uncle’s Murder series, 2008

Police Sketch of the Murder, My Uncle’s Murder series, 2008

Blood Spattered Documents, My Uncle’s Murder series, 2008

My Mothers Signature, My Uncle’s Murder series, 2008

No Chinese Flag, 2008

inkjet print—Epson UltraChrome K3™ inks on Innova Softex 315 gsm paper

Presentation at the 24th Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous assistance from Simon Chan AM Art Atrium

Courtesy the artist

“To write a good story,” William Yang tells the young artists who come to him for advice, “you have to bleed a little.” Indeed, across a career defined by unshrinking documentation of Australian culture, Yang has created an exceptionally vulnerable body of work.

Yang was born near Cairns in Queensland, a state that owes much to the contributions of the Chinese immigrants who made it their home following the gold rush. By the 1920s, despite having established the banana and sugarcane industries that supported the region, the White Australia Policy decimated the economic and cultural freedoms of the Chinese community in Queensland.

In the series ‘My Uncle’s Murder’, Yang tells the story of William Fang Yuen’s murder in 1922 at the hands of a White plantation manager. Using archival material and photographs, Yang memorialises not only the steep price of agricultural progress in modern Australia, but those whose blood paid for it. In one portrait, the artist stands in the place where his uncle died, staring defiantly down the lens, balancing the pain and pride innate to the diasporic experience.

Chau Chak Wing Museum

Malcolm Cole. Circa 1976, Glebe, 1976 (reprinted 2024)

photographic print

On tour after hours, 1976 (series)

photographic prints

Pictured: Wayne Nicol, Malcolm Cole, Cheryl Stone and Kim Walker

Michael Leslie, Dubbo from AIDT Performance Dubbo, 1976 (series)

phototex

Forward to the Dreamtime performance. Sydney Opera House, 1976 (series)

photographic prints

Pictured: Malcolm Cole (deceased), Andrea Coleman (deceased), Rosemary Evans (deceased), Michael Leslie, Leonie Malamoo, Philip Langley (deceased), Richard Talonga, Steven Talonga, Sharon Coffee a.k.a. Ruby Dykes, Anne Gundy, Cheryl Stone, Johnny Williams, Darrell Williams and Wayne Nicol

Forward to the Dreamtime performance. Sydney Opera House, 1976

photographic print

Workshop by Erik Mariko, Arthur Keibsu and Peter Kikaki, Glebe Studios, 1976 (series)

photographic prints

Pictured (clockwise): Michael Leslie, Malcolm Cole, Dorethea Randall, Richard Talonga, Cheryl Stone, Kim Walker, Wendy Sue Roberts, Lillian Crombie

Michael Leslie, Dorethea Randall, Richard Talonga, Wendy Sue Roberts, Malcolm Cole, Cheryl Stone, Kim Walker

Malcolm Cole, Rosemary Evans, Michael Leslie, Andrea Coleman, Leonie Malemoo, Philip Lanley, Richard Talonga, Steven Talonga; Ruby Dykes, Annie Gundy, Carol Y. Johnson, Cheryl Stone; Johnny Williams, Darryl Williams, Wayne Nicol

Michael Leslie, Dorethea Randall, Malcolm Cole

Lillian Crombie sadly passed away on January 3rd, 2024. The Biennale of Sydney sends condolences to her family

Michael Leslie, Dubbo from AIDT Performance Dubbo, 1976 (series)

phototex

In 1976, four years after the Aboriginal Tent Embassy occupied the lawns of Parliament House in protest of the government Land Rights policy, a troupe of Indigenous performers were beginning to reshape Australian choreography and dance.

Led by African American dancer and cultural manager Carole Y. Johnson, AISDS (Aboriginal/ Islander Skills Development Scheme), and its student ensemble AIDT (Aboriginal/ Islander Dance Theatre), was a platform for the rejuvenation of Indigenous dance language, a catalyst for exploration into the possibilities of contemporary movement and a cultural firebrand. Tackling issues such as the experiences of the Stolen Generation (government sanctioned abductions of Indigenous children that took place from the mid-1800s to the 1970s), the company’s approach to performance confronted the contradictions and tensions seen in Australia, a country yet to come to terms with its colonial legacy.

In 1968 Malcom Cole, an Aboriginal and South Sea Islander man from Far North Queensland, left his hometown of Ayr (Queensland) for Warrang (Sydney), where he would ink an indelible mark on the creative and queer history of Australia.

A founding member of AIDT, now NAISDA (the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association), Cole radically interrupted the largely white dominated framework of Australian dance and performance. In 1988 he was the first Indigenous Australian to host a float in Sydney’s Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade. There (along with artist Panos Couros), he recreated the 1788 landing in Botany Bay dressed in drag as a Black Captain Cook, who was hauled down the street by a group of white convicts.

Working as a prolific dancer and mentor, Cole was invited to participate in the First National Aboriginal HIV/AIDS Conference in Mparntwe (Alice Springs) in 1992. Three years later, he would die from HIV/AIDS in the care of his brother, Robert.

With a dancer’s grace, Cole trod a path first marked out by the ancestors who preceded him. This path, hewn again by those who have followed in his footsteps, has wound its way into the heart of creative Australia.

Presentation at the 24th Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous assistance from Simon Chan AM Art Atrium

Courtesy the artist and State Library New South Wales