Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney

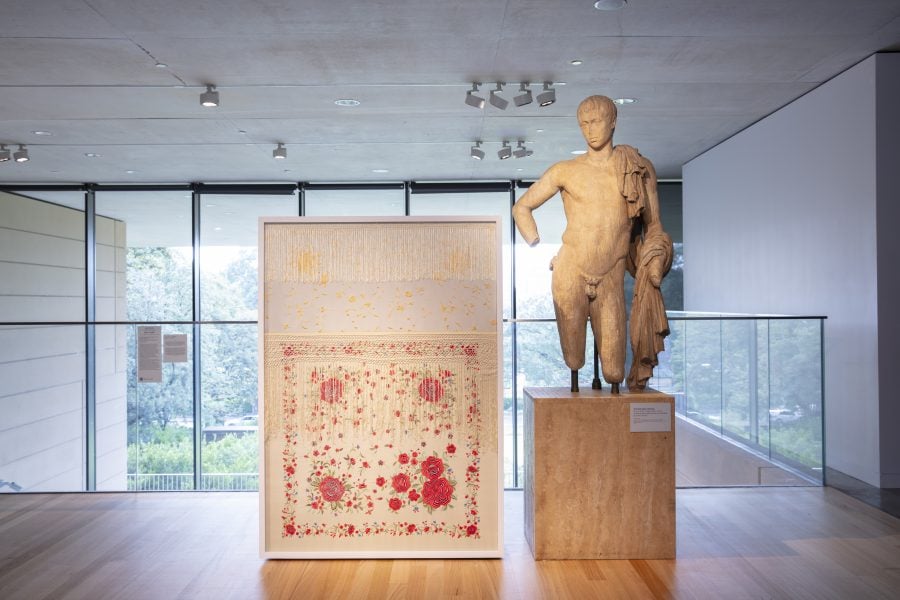

O sea, sadopítna-antípodas, puesto del revés y boca abajo (sedopitna-antipodes, turned inside out and upside down), 2023 (suite of 4)

sound, timber, Manila shawls

Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney and Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA) and with assistance from Accion Cultural Española

Courtesy the artists

O sea, antípodas, puesto del revés y boca abajo (antipodes, turned upside down and upside down) uses flamenco music and history to interrogate trade and colonisation as both shaping and corrosive forces. Creating a ‘map’ of sound, flamenco performer Niño de Elche and artist Pedro G. Romero chart composite communities over nine songs from several cultures, linked in various ways to flamenco. Following antipodean connections and old Galleon Trade routes, the songs travel from Mexico, Thailand, the Philippines, Japan, Indonesia, Aotearoa New Zealand to Samoa, traversing a strange archipelago where each island is united by the sea that separates them.

Unfolding the subaltern resonance of flamenco shawls (Manton de Manila), a hybrid commodity of Spanish culture and colonial trade, O sea, antípodas, puesto del revés y boca abajo is literally and symbolically projected through a filter of flamenco, which is also a filter of postcolonialism. Growing from the wounds left by history Niño de Elche and Romero, from the position of flamenco, at once colonised and colonising, subvert ideas of creation and corruption to create a unique discordant chorus, at once bleeding and blooming.

I. “Song of thieves—better beg than steal—or mariana, from the time of Pepe Marchena, when the maestro gave us a Song of Ecuador and the Song of Guatemala, a milonga known as Canción Mexicana as well as colombianas, and all of this, which springs from exchanges between Spain and Latin America, became known as ‘cantes de ida y vuelta’ (flamenco is inherently Atlantic), with the knowledge that these songs—or ‘palos’—reveal a colonial construction that led Maestro Andujar, in caricature, to look for an origin of the mariana in the islands of the same name, the Mariana Islands , formerly Islas de los Ladrones (Islands of Thieves), named in honour of Queen Mariana of Austria, just as the Caroline Islands were named after Charles II of Spain and the Philippines after King Philip II of Spain, thus opening a path for a flamenco of the Pacific Ocean.”

II. Wedding song of the ‘gitanos del mar’ or ‘sea nomads’ of Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia, that is, the Moken, Bajau and Orang Laut people, who are not Roma-gitano but who have been attributed with certain customs—nomadic, revellers, lumpen and aristocratic at the same time—that adjectivally link them (from the Eurocentric Western perspective, since the time of the Arabs) with ‘gitanos’, being described as such and comparable in their traditions to Spanish gitanos—thus connecting them to flamenco, among other things—all of which leads us to say that anyone who has not hunted swallows nests in the ‘gitano’ way, and who does not belong to the ‘gitano’ communities of Sapam, Rawai and Phuket—akin to the triangle of Lebrija, Utrera and Jerez—or fished as ‘gitanos’ do from the bottom of the sea—the eyes and lungs of the sea ‘gitanos’ have adapted to the underwater world—, anyone who has not taken part in three or four ‘gitano’ weddings and who has not eaten duende—they cook and eat their jinns or duende-spirits—, in other words, anyone who is not ‘gitano’ and not from, for instance, Sapam, Rawai or Phuket, cannot truly understand the ‘gitano’ wedding song.”

III. “Petenera song that Padre Dámaso sings in Noli me tangere—it is sung constantly in José Rizal’s novel of Philippine independence— just before the Corpus Christi mass that kindles the flame of freedom in the revolutionaries and leads to, among other things, the famous apocryphal Kundiman, love songs that call for the beloved to be freed from the chains of slavery, even the slavery of love.”

IV. “Tangos, tientos-tango, or extremely slow tientos song of the maestro Kazuo Onō, who, as a disciplined gymnastics teacher, was moved to start dancing when he saw Antonìa Mercè ‘La Argentina’ perform in Tokyo, and who ended his career dedicating ‘La Argentina Shō’ to his Spanish inspiration—Kazuo was able to withstand the war in China, New Guinea and the concentration camps in Australia only by remembering La Argentina!—helped by his friend and accomplice Tatsumi Hijikata, with whom he had started to develop Butō dance as a way of confronting the horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the helter-skelter order that Fat Man and Little Boy brought into the world.”

V. “Zambra song of the shellac secreted on trees in the Indonesian archipelago, which fuelled the manufacture of 78 rpm records—known as ‘pizarra’ (slate) in flamenco, perhaps because of their similarity to school blackboards—and which served to crystallize the cañí genre— as it did the blues, the Cuban son, and tango—, to solidify the myth of the vernacular, and to invent tradition and write the canon, as Michael Denning explains in his book Noise Uprising, before this phenomenon crashed with the Great Depression of 1929, punishing and impoverishing the popular classes on their path to emancipation.”

VI. “Alegrías song of infinite sadness, as heard on the soundtrack of Ein No Hito-Immortal Love, also known as The Bitter Spirit, an emotional drama by Keisuke Kinoshita—Japan’s first openly gay film director—with music by Chuji Kinoshita played by José Shoda, the first Japanese flamenco guitarist (a way into better understanding the flamenco fiesta in Shôhei Imamura’s The Eel), who strums and embellishes the sound of his guitar with infinite depth, like that of the smoking volcano crater that compels all the protagonists to grapple with the past in lives marked by tragedy.”

VII. “Granaína and soleá song by Japanese composer Teiji Ito for Marie Menken’s film Arabesque for Kenneth Anger—which she filmed in the Alhambra on a single day in 1958, and for which Ito did not write the score until 1961—, while Luciferian Californian filmmaker Anger may have been familiar with the Granadan filmmaker and mystic José de Val del Omar’s film Water-Mirror of Granada—which Menken also appears to pay homage to (although she did not actually know Val del Omar, but she did know Ito)—, a song also of the various reflections that this mirage gave rise to in the counterculture of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.”

VIII. “Soleá song of Darcy Lange and Miriam Snijders, who dedicated Aire del Mar—their first multimedia ecological opera—to fighting for the rights of the Māori people and protesting against the French nuclear testing in the Pacific and the ensuing destruction of a particular ecosystem and the forms-of-life and relationships that sustained it, and did so using the flamenco of Diego del Gastor, who had taught Lange guitar in Morón de la Frontera, in the shadow of the North American military base of the same name, which—there too—makes the skies tremble.”

IX. “Song of the zapateado footwork of Lemi Ponifasio, the Samoan director who presented Love to Death in 2020, a performance in which he works with a Mapuche singer and with a flamenco dancer who represents Chile, no less, so that flamenco—a guacho, bastard, indeed always delinquent, art form—adopts here, by way of the Spanish cliché, the role of police, of patrolling Guardia Civil, an element that, alas, is also already present in its DNA.”