UNSW Galleries

The Sound of Silence, 2024

rubab instruments fabricated by Hossein Shirzad; neon

Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney and Art Jameel

Courtesy the artist

In The Sound of Silence, Elyas Alavi has overlaid neon text onto four rubab instruments in a reimagining of the songs and poems that may have accompanied the cameleers on their travels. The excerpts reference four different dialects, acknowledging the diversity of languages spoken by the cameleers, and are translated below:

The camel rider will set off (then you’ll rove in desperate search of your beloved)

Saraiki language: Excerpt of an old folk song from the Saraiki Baloch people of Pakistan.

Let’s go to the city of Mazar Mulla Mohammad Jaan!

Farsi/Dari language: Excerpt of an old folk song by an unknown female poet from Herat, Afghanistan.

I’m a lover and love is the only thing I know

Pashtu language: Excerpt of a poem by renowned poet Rahman Baba.

I seem to have loved you (in numberless forms, numberless times)

Hindi language: Excerpt of a poem by Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.

But you are my home, 2024

video, sound, colour

Audio includes music by rubab player Nasim Khoshnavaz and voice of Naria Nour

Ringing out across national borders, the music of the Afghani rubab instrument has scored the desert of central Australia for generations.

Between 1860 and 1920, Australia relied upon mostly Islamic cameleers primarily from South Asia, as well as Southwest Asia and North Africa. Known as ‘Afghan’ cameleers, these men came from diverse backgrounds to transport supplies, communication infrastructure, and colonial society between regional outposts. It was these men who built the Overland Telegraph Line, linking Adelaide to Darwin (and subsequently the British Empire), and the Trans-Australian Railway across the Nullarbor. Yet the cameleers were vilified by the media of the time, and suffered discrimination in government policy, being granted only temporary visas and refused naturalisation. As they traversed the nation’s interior, their tracks intersected with those that had already been established by First Nations peoples, and so formed an intercultural bond.

The descendants of marriages between cameleers and Indigenous people of Australia now make up a portion of the keepers of the oral history investigated by artist Elyas Alavi in The Sound of Silence. Honouring the stories and songs of the cameleers, Alavi memorialises the wisdom and philosophy the cameleers carried in their music and on their camels’ backs.

Through archival research and fieldwork, Alavi detects parallels between the restrictive conditions endured by early cameleer communities and the contemporary reality for Afghan and Middle Eastern diasporas throughout Australia. Singing out in the face of the enduring impact of the White Australia Policy, The Sound of Silence both delights in and divulges the forgotten legacy of the cameleers.

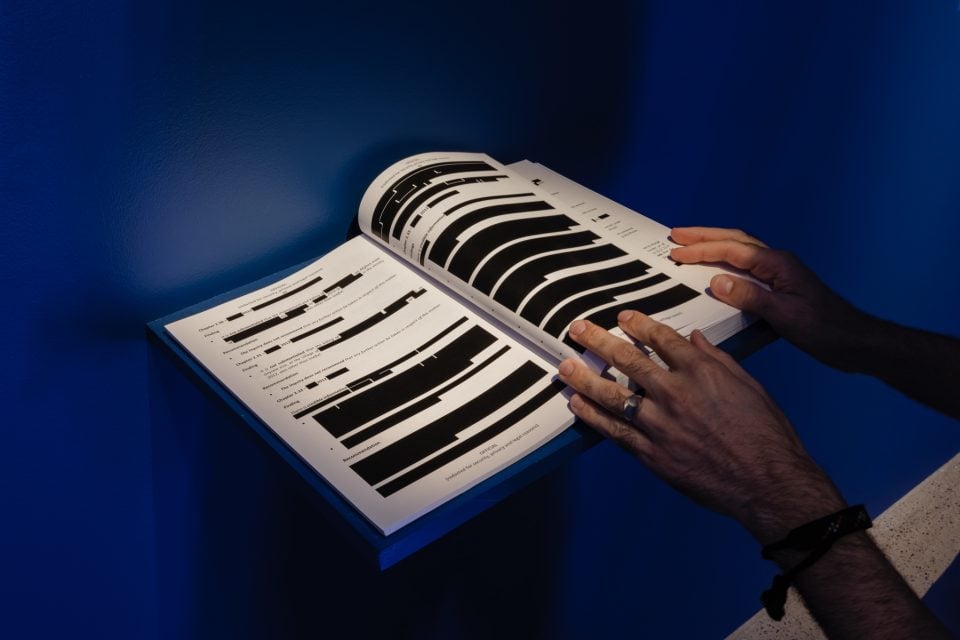

BLOODING (series), 2023

ink, pencil, artist’s own blood, found images on found newspapers, printed Brereton report

Courtesy the artist

BLOODING is inspired by the Brereton Report on war crimes allegedly committed by the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The report found evidence of at least 39 murders of Afghan civilians and prisoners by (or at the instruction of) members of the Australian Special Force, which were subsequently covered up by ADF personnel. These killings began in 2009, with most occurring in 2012 and 2013. The inquiry found that junior soldiers were often required by their superiors to murder prisoners to get their first kill, a practice known as ‘blooding’.

VASL (series), 2024

photographic print with paper collage

Courtesy the artist

In VASL, Alavi juxtaposes photographs documenting landscapes across Afghanistan and the Australian outback. As the curves of the mountains of Afghanistan merge with those of the Australian desert, Alavi highlights the invisible connections between the two locations which both hold significance to the history of the cameleers.

Neshani (Keepsakes) c.1970/2013

beaded necklace; beaded mirror; woven and beaded hat

Neshani are handmade objects often given to a loved one, especially those who are embarking on a long journey. These intricately beaded objects were made in the Daikundi Province of Afghanistan and gifted to Elyas Alavi by family members. They are similar to the objects that accompanied the cameleers on their journeys.

By Compass and Quran: History of Australia’s Muslim Cameleers, 2024

video excerpt

Writer/Director: Kuranda Seyit

Producer: Fadle El Harris

Photographic documentation of the cameleer’s everyday activities in Broken Hill, NSW, and Marree, SA from the early 1900s.

Photo: unrecorded maker

Private collection of Amminullah Shamroze

Photo: unrecorded maker

Private collection of Amminullah Shamroze

Photo: unrecorded maker

Private collection of Amminullah Shamroze

Cameleer descendant and musician.

Photo: Elyas Alavi

Cameleer descendant Aleema Sediq with a qichack musical instrument.

Photo: Pamela Rajkowski

Only remaining rubab musical instrument brought by cameleers currently held in the Mosque Museum, Broken Hill.

Photo: Elyas Alavi

Portrait of Kie Shirdel, the cameleer musician and owner of the rubab held in the Mosque Museum, Broken Hill.

Private collection: Amminullah Shamroze

Gravestone at the cameleer section of a cemetery in Marree, SA.

Photo: Elyas Alavi

Notebook belonging to cameleers.

Photo: Elyas Alavi

Collection: Mosque Museum, Broken Hill.

Annual camel racing known as the Marree Camel Cup in South Australia.

Photo: Elyas Alavi

Mosque built by cameleers in Adelaide, SA.

Photo: Elyas Alavi

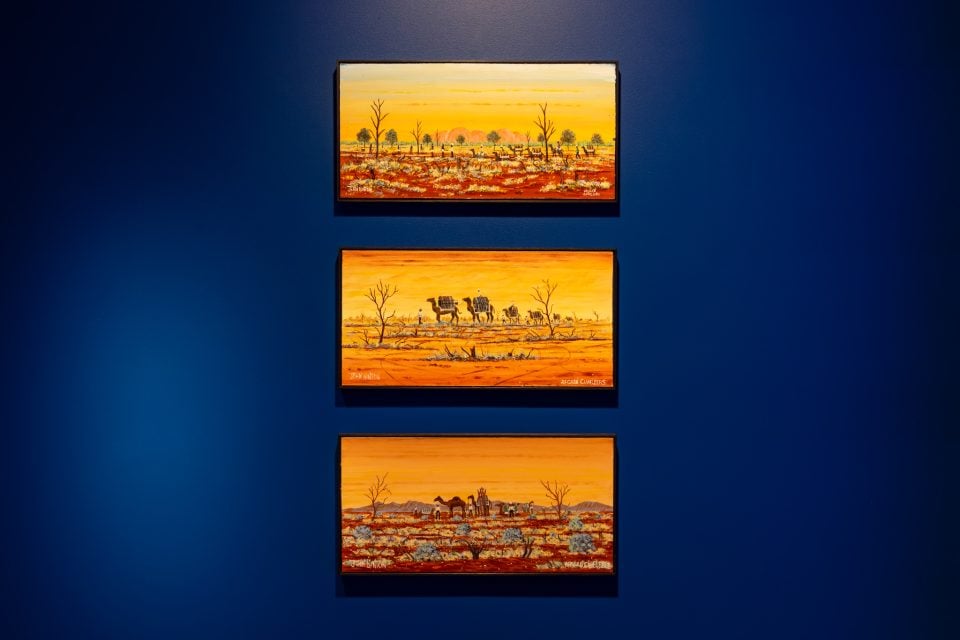

JOHN HINTON

Afghan Cameleers (series), 2022

acrylic on board

Courtesy the artist

JIM HINTON

Cameleers (series), 2023

acrylic on canvas

Courtesy the artist

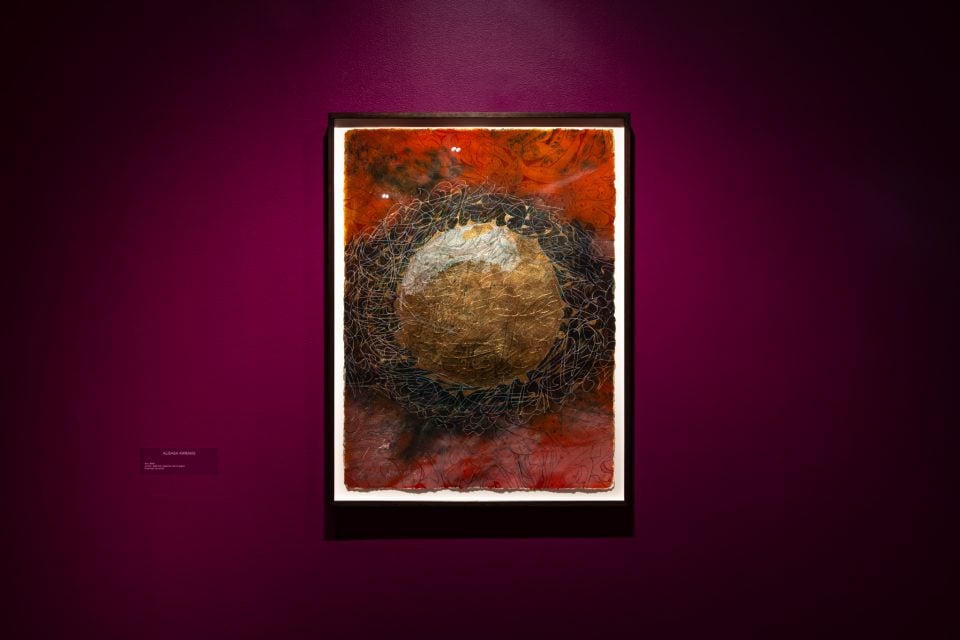

ALIBABA AWRANG

SUN, 2023

acrylic, gold leaf, Japanese ink on paper

Courtesy the artist